Who This Guide Is For (And Why Uptime Claims Feel So Confusing)

Hosting uptime suddenly becomes interesting when a website or application is no longer “nice to have”. Perhaps your brochure site is now a key source of leads, your WooCommerce store takes real revenue every hour, or partners depend on an internal portal to do their jobs.

This guide is for people in that position:

- Owners and managers of growing businesses

- Marketing and digital teams responsible for a website

- Technical generalists who “look after the servers” but are not full time infrastructure engineers

The aim is to help you read uptime guarantees with a clear head, understand what they really mean in practice, and decide what is appropriate for your level of business risk.

When uptime suddenly matters to the business

For many organisations, the journey looks like this:

- A simple brochure site on shared hosting, with little concern about a few minutes of downtime.

- More marketing campaigns, paid ads and SEO work, so the site becomes a primary lead source.

- Online payments, bookings or a customer portal, where any outage means lost revenue or angry calls.

At each step, the “cost” of downtime grows. It might be:

- Lost sales or cart abandonments

- Leads that never reach your CRM

- Staff unable to work efficiently

- Reputational damage when an outage is very visible

Often, the first response is to look at hosting plans that quote higher and higher uptime percentages. That is understandable, but the numbers can be misleading without context.

The problem with marketing numbers in hosting

Hosting is full of attractive round numbers: 99.9%, 99.99%, even “five nines”. They appear scientific and precise, which makes them reassuring on a sales page.

The confusion usually comes from three issues:

- Different providers mean different things when they write “uptime”, even if the percentage is the same.

- The guarantees usually apply only to part of the stack, such as power and network, not your application itself.

- Compensation is typically very limited and paid as credit, not cash, even if the disruption cost you far more.

On top of that, infrastructure design and day to day operations matter at least as much as the number printed in the SLA. We will come back to this, but it is worth keeping in mind from the start.

Plain English: What Uptime Actually Is

Availability vs uptime vs reliability

In everyday conversation people mix “uptime”, “availability” and “reliability” quite freely. They are related but not identical:

- Uptime is the proportion of time a service is running and reachable. Usually expressed as a percentage over a month or year.

- Availability is similar, but often used more broadly, including whether users can actually complete tasks, not just reach the homepage.

- Reliability focuses on how frequently things fail and how predictable the system is over time.

Many hosting SLAs use “availability” in the legal text, but the headline figure behaves like uptime: time the core service is up, divided by total time in a defined period.

How uptime is really measured over a month or year

At its simplest, uptime percentage is:

Uptime % = (Total time − Downtime) ÷ Total time × 100

where “downtime” is the accumulated minutes when the service is classed as unavailable.

The important nuance is how “downtime” is defined in the SLA. Common details include:

- Measurement period: per calendar month is typical, sometimes quarterly or per year.

- Measurement point: for example, is uptime measured at the network edge, the server, or at your web application port.

- Outage thresholds: some providers only count outages longer than a certain period, such as 5 or 10 minutes.

- Exclusions: planned maintenance, DDoS attacks, customer mistakes and similar events are often excluded from the calculation.

Two providers could both claim “99.9% uptime” and yet count downtime quite differently.

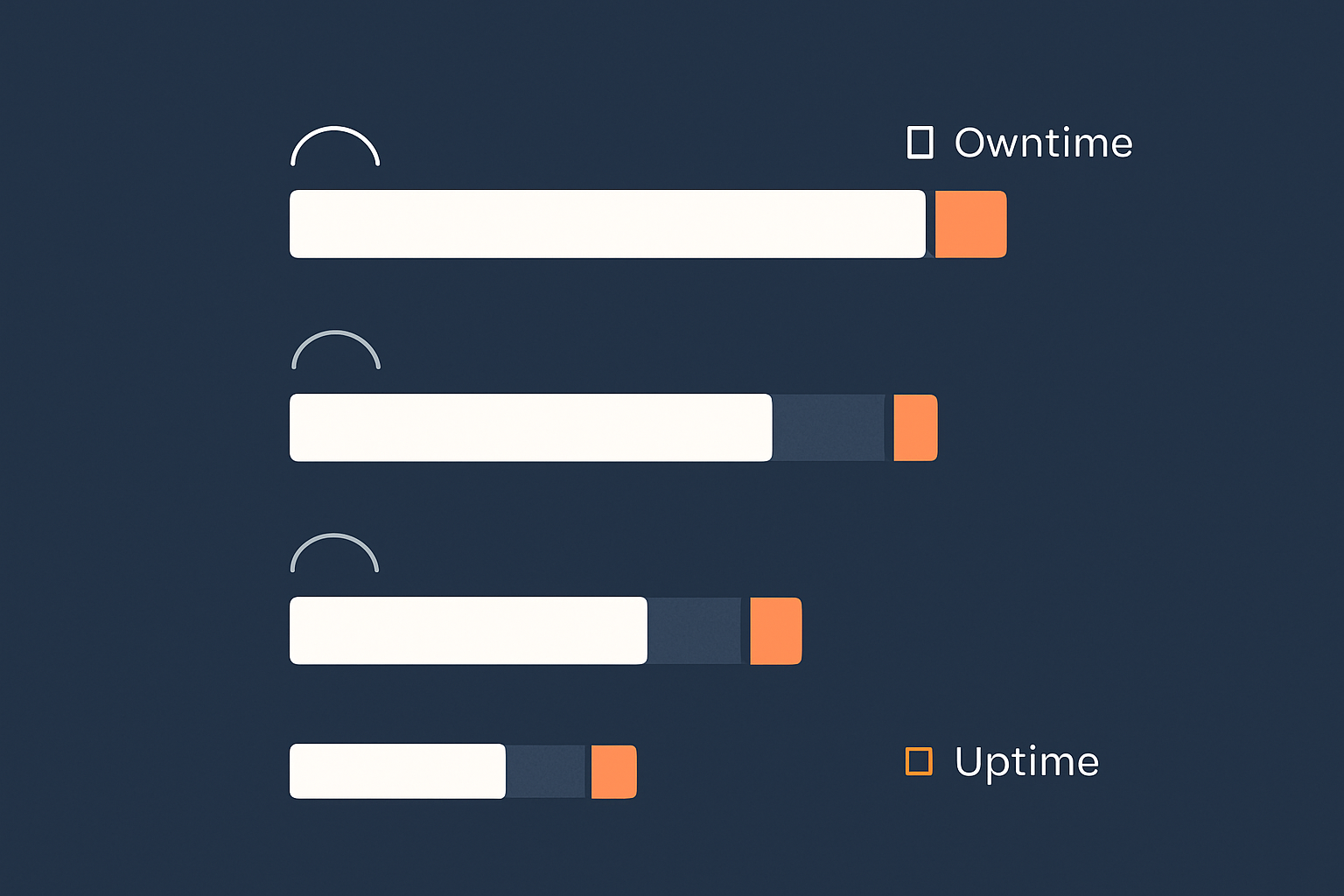

What different uptime percentages mean in minutes of downtime

To make the percentages more concrete, here is what they roughly mean over a year:

- 99% uptime: up to about 3.65 days of downtime per year.

- 99.5% uptime: up to about 1.8 days per year.

- 99.9% uptime: up to about 8 hours 45 minutes per year.

- 99.95% uptime: up to about 4 hours 23 minutes per year.

- 99.99% uptime: up to about 52 minutes per year.

- 99.999% uptime (“five nines”): up to about 5 minutes per year.

Even 99.9% still allows several hours of downtime per year, which may arrive in one very visible incident. Conversely, achieving 99.99% consistently normally requires careful design, monitoring and operations, not just a different hosting plan.

When you see a percentage, translate it into a maximum acceptable downtime window and ask yourself: would that be acceptable if it all happened in one go, at a busy time?

The Allure of “Five Nines” Uptime (And Why It Is Rarely What You Think)

What 99.9%, 99.95% and 99.99% actually look like in real time

It can help to think in monthly terms, because that is how most SLAs are structured.

- 99.9% in a 30 day month allows about 43 minutes of downtime.

- 99.95% allows about 22 minutes.

- 99.99% allows about 4 minutes 20 seconds.

For an online shop, 43 minutes of outage at 8pm on a Sunday in December will feel very different to four separate 10 minute blips at 3am in August. The SLA treats both months as “within target”. Your business probably does not.

This is one of the reasons why chasing ever higher percentage numbers alone can be misleading. The pattern, predictability and timing of downtime matter just as much.

Why true “five nines” is an engineering project, not a tariff name

“Five nines” means a service can be down for at most about 5 minutes in a year. Achieving that in reality usually requires:

- Multiple layers of redundancy for power, network and hardware

- Clustering or high availability at the application level

- Automated failover and tested recovery procedures

- Mature monitoring, alerting and incident response

- Careful change control and staged deployments

This is not something that appears automatically because marketing copy on a shared hosting plan mentions “five nines”. It is a design and operational commitment across the stack.

At the infrastructure level, very high availability is often built using technologies such as clustered databases, replicated storage, high availability load balancers and redundant network paths. On top of that you need application level resilience and good practices around code changes.

If you are considering a “five nines” style claim, it is reasonable to ask how that figure is achieved in practice and at what level of the stack it actually applies.

Where five nines does make sense: payments, healthcare and critical systems

There are environments where investing heavily in very high availability is justified, for example:

- Payment gateways and card processing platforms

- Healthcare systems used in clinical settings

- Industrial control systems and critical national infrastructure

In these cases, the cost and effort of engineered high availability can be justified by the risk of failure. For example, card brands and regulators expect strong technical and procedural controls around availability and security. If you operate an ecommerce platform that handles card data directly, you may be looking for PCI conscious hosting for payment and compliance sensitive sites as part of your approach.

Most business websites do not need true five nines throughout the year. They need sensible, honest SLAs, and an architecture aligned with the real cost of downtime to the business.

Common Myths and Misconceptions About Uptime Guarantees

Myth 1: An uptime guarantee means your site will not go down

An uptime guarantee is not a promise that outages will not happen. It is usually a commitment that the provider will aim for a certain level of availability and offer specific credits if they fall short, within the defined scope.

Your site can still go down for many reasons outside that scope, such as:

- Application bugs or misconfigurations

- CMS or plugin updates that introduce errors

- Third party API failures

- Traffic spikes beyond what the hosting plan can handle

The guarantee is about infrastructure reliability, not an absolute insurance policy against any incident.

Myth 2: The SLA covers everything from the data centre to your code

Most uptime SLAs cover a limited part of the stack, often described as “network and power” or “infrastructure availability”. It is less common for a standard SLA to include your operating system configuration, application stack or code.

For example, if the data centre network is functioning but your WordPress plugin update breaks the site, that downtime is not usually counted for SLA purposes.

Some managed services will take on responsibility further up the stack, such as managing the web server, PHP and database, and providing application level monitoring. This is one of the areas where Enterprise WordPress hosting with defined SLAs or similar managed platforms can reduce the amount of operational risk you carry directly.

Myth 3: Refunds for downtime make you financially whole

Uptime guarantees often mention service credits if downtime exceeds certain thresholds. These can be useful, but it is important to set expectations:

- Credits usually apply only to the affected hosting service fee, not your wider business losses.

- They are normally capped at a fraction of the monthly bill.

- They are rarely offered automatically; you may need to submit a claim within a set time.

- They are provided as hosting credit, not cash.

If your ecommerce site loses thousands of pounds in sales during a one hour outage, a credit on a relatively modest hosting bill is welcome but not a full remedy. The real protection is in the architecture and operations that reduce the chance and impact of outages in the first place.

Myth 4: Backups or a second server automatically mean higher uptime

Backups are vital, but they are about recoverability, not uptime. They help you restore data after an incident. They do not keep your service available while a failure is in progress.

Similarly, having a second server only improves uptime if:

- It is correctly configured for redundancy or failover

- There is a mechanism to route traffic to it automatically or quickly

- You have tested the failover process

Our article Backups vs Redundancy: What Actually Protects Your Website goes into this distinction in more depth. The short version is that backups, redundancy and disaster recovery each solve different problems, and you usually need a combination tailored to your risk tolerance.

What Uptime SLAs Usually Cover (And What They Quietly Exclude)

The typical SLA scope: network and power vs full stack

A typical basic hosting SLA might say something like “we guarantee 99.9% uptime for our network and power”. That usually means:

- Redundant power feeds, UPS and generators in the data centre

- Redundant network connections from the facility to the internet

- Monitoring of those core services

More advanced SLAs might extend to:

- Hypervisor or virtualisation layer availability

- Host node hardware replacement times

- Storage system availability

It is less common to see standard SLAs that include:

- Operating system uptime on your specific server or virtual machine

- Database and web server availability

- Your application or CMS behaviour

For that level of coverage, you are generally looking at more tailored managed services, where the provider takes responsibility for larger parts of the stack. Our article on hosting responsibility and what your provider does and does not cover explores these boundaries in more detail.

Planned maintenance, force majeure and other exclusions

SLA documents also contain a list of events that do not count towards downtime for the purpose of the guarantee. Common exclusions include:

- Planned maintenance: routine work that is announced in advance within given windows.

- Force majeure: events beyond reasonable control, such as major natural disasters.

- Customer actions: misconfigurations, DDoS attacks caused by your own outbound traffic, or code related incidents.

- External provider failures: for example, your DNS provider or third party APIs.

These exclusions are not inherently unreasonable, but they do mean that the headline uptime figure only tells part of the story. When comparing providers, pay as much attention to the exclusions as to the promised percentage.

How credits actually work in practice

Credit mechanisms can vary, but typically:

- There is a table mapping downtime ranges to a percentage of monthly fee credited.

- You must open a support ticket within a certain period after the incident to claim.

- Credits are applied against future invoices only.

- If multiple components are affected, there may be a cap on total credit.

Consider credits a signal of the provider’s confidence and willingness to share some downside, not a replacement for your own risk assessment and continuity planning. For more structured guidance, see From Backups to Business Continuity: Building a Realistic Disaster Recovery Plan with Your Hosting Provider.

Reading SLA fine print without being a lawyer

When you read an SLA, you do not need to understand every legal phrase. Focus on a few key questions:

- What exactly is covered by the uptime guarantee?

- Over what period is uptime measured, and how is downtime defined?

- What are the exclusions, and do any of them worry you?

- What is the process for claiming credits, and are they meaningful in value?

- Does the SLA align with how critical the service is to your business?

It can be useful to compare how different providers answer those points, rather than only scanning for the highest percentage.

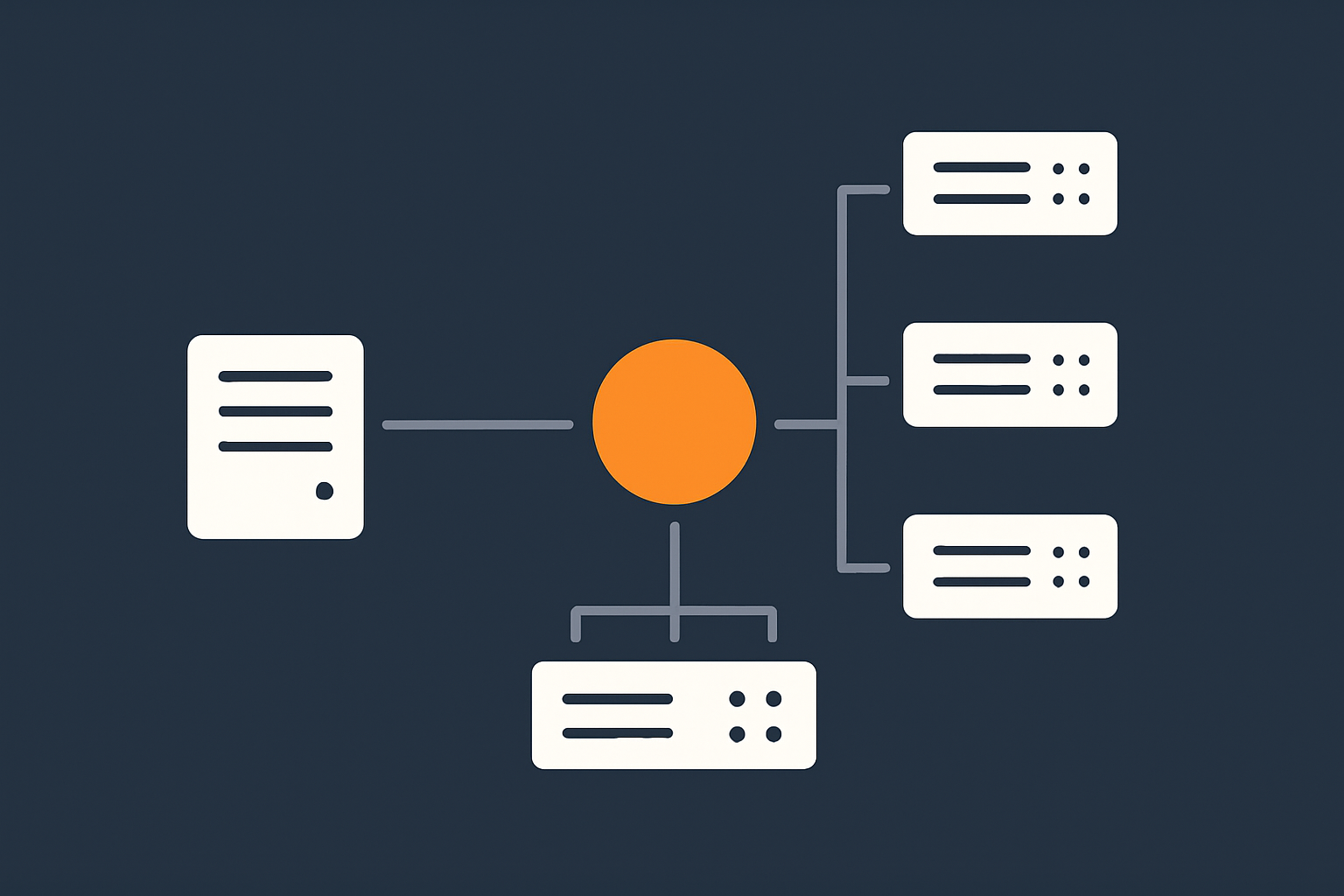

Architecture Matters More Than a Percentage: How Your Setup Affects Real Uptime

Single server vs high availability: what changes for uptime

Imagine two scenarios:

- A single powerful server running your entire site.

- Two smaller servers behind a load balancer, with shared or replicated storage.

Even if both are hosted with an infrastructure provider quoting the same SLA percentage, their real world behaviour during faults can be quite different.

With a single server, if that machine fails, your whole site disappears until it is repaired or rebuilt. With a high availability setup, other nodes can continue serving traffic while the faulty one is replaced.

Designing and operating high availability environments is more complex. It is a good fit when downtime would be very costly and you have, or can access, the operational skills to run it. If your team is small, using virtual dedicated servers for higher reliability and isolation or managed clusters can be a way to improve availability without bearing all the complexity in house. Our article High Availability Explained for Small and Mid Sized Businesses covers practical options in more depth.

Redundancy vs backups vs disaster recovery

These three concepts are often conflated, but they solve different problems:

- Redundancy is having spare capacity or duplicated components ready to take over instantly or quickly when something fails. It protects uptime.

- Backups are copies of your data taken on a schedule. They protect against data loss, not short outages.

- Disaster recovery is the plan and infrastructure to recover service in another location or environment after a major incident.

For example, a second database node in a cluster is redundancy. A nightly database dump stored offsite is a backup. A replicated environment in a different region that can be activated if the primary data centre is lost is part of disaster recovery.

A robust hosting setup will typically use all three, in proportion to the impact of downtime and data loss on the business.

How network, storage and DNS design affect downtime risk

Application servers are only part of the picture. Other layers contribute significantly to uptime:

- Network: Single points of failure in switches, routers or upstream connections can take down otherwise healthy servers.

- Storage: If all data is on a single storage device, a failure there can be as disruptive as a server failure.

- DNS: Poorly configured or single provider DNS can make your site unreachable even when hosting is fine.

Good hosting providers design their core network and storage with redundancy, and many businesses run multi provider DNS for resilience. For organisations that do not want to design this in detail, managed services or curated platforms can provide a sensible default architecture that balances availability, cost and complexity. Our article Designing for Resilience: Practical Redundancy and Failover When You Are Not on Public Cloud walks through some realistic patterns.

Choosing the Right Level of Uptime for Your Business Risk

Translating downtime into lost sales, leads and reputation

To choose an appropriate uptime target, work backwards from business impact. Ask:

- How much revenue does the site generate per hour at busy times?

- What is the average value of a lead, and how many could we lose in a 1 hour outage?

- Would downtime at certain times (for example, during live events or campaigns) be especially damaging?

- Would regulatory or contractual obligations be affected by outages?

It can help to put rough numbers on these. For example, if your store averages £1,000 per hour in sales at peak, then a 2 hour outage could cost around £2,000 in direct revenue, plus some secondary effects from lost customer confidence.

Deciding whether you need 99.5%, 99.9% or “as close as possible”

Once you have a sense of impact, you can think about tiers of availability as policy decisions, such as:

- “We are comfortable with occasional short outages” for internal tools or low traffic brochure sites. Lower cost hosting with basic redundancy and a realistic SLA may suffice.

- “We need strong uptime, but not mission critical levels” for lead generation sites and growing WooCommerce shops. Higher quality infrastructure with clear SLAs and basic high availability patterns is often appropriate.

- “We need to minimise downtime aggressively” for platforms with high direct revenue or contractual obligations. Here, architecture, monitoring, managed services and higher SLA tiers all come together, and you are designing towards “as high as reasonably achievable” rather than a single number.

There is no universal right answer. The key is that the uptime target, the architecture and the budget all line up.

Different needs: brochure sites, lead generation, WooCommerce and enterprise workloads

To make this more concrete:

- Simple brochure site

A few hours of downtime a year is unlikely to be catastrophic. Shared hosting with sensible backups and security can be perfectly adequate, especially for smaller organisations. - Lead generation site

Outages during campaigns hurt more. Investing in better infrastructure, monitoring and at least some redundancy is often worthwhile. - WooCommerce or subscription site

Downtime means direct loss of sales and support overhead. A more considered setup, with managed elements, redundant components and performance optimisation, is usually justified. - Enterprise workloads or multi tenant platforms

Here you are often dealing with SLAs to your own customers. Architectures with multiple web hosting security features that reduce outage risk, strict change control and well tested recovery plans become the norm.

In all cases, the aim is to be deliberate. Accepting some downtime can be a rational decision if the cost of extremely high availability would outweigh the benefit.

What Actually Improves Uptime (Beyond a Higher SLA Number)

Monitoring and alerting: knowing something is wrong quickly

You cannot fix a problem you do not know about. Practical uptime depends on:

- External monitoring of key endpoints, such as your homepage and checkout.

- Internal monitoring of server resources, such as CPU, memory, disk and database status.

- Alerting that reaches the right people promptly, through email, SMS or chat.

Many providers offer basic monitoring, but you may still want your own independent checks, especially for business critical paths such as login and payment flows.

Capacity planning and performance: avoiding “slow equals down”

Users often experience a very slow site as effectively “down”, especially on mobile. Performance and capacity planning are therefore part of uptime.

Key elements include:

- Ensuring your hosting resources are sufficient for peak load, not just average load.

- Using caching to reduce the load on application servers.

- Optimising images and static assets to reduce bandwidth and processing needs.

- Filtering abusive or automated traffic that can overwhelm your site.

For sites serving a global audience or heavy media content, a content acceleration layer can make a substantial difference. The G7 Acceleration Network is an example of this type of service: it caches static content close to end users, converts images on the fly to efficient formats such as AVIF and WebP (often reducing image sizes by more than 60 percent), and filters abusive traffic before it reaches your application servers. The result is both faster performance and less strain on your origin infrastructure, which supports higher real world availability.

Maintenance, patching and sensible change control

Many outages arise from changes rather than underlying hardware failures. Good operational hygiene can significantly improve uptime:

- Regularly applying security and stability patches to the operating system and software stack.

- Scheduling maintenance during agreed windows with low user impact.

- Testing changes in a staging environment before deploying to production.

- Having a rollback plan if a deployment causes problems.

This is an area where even technically capable teams can struggle if they have limited time. Being disciplined about change control reduces the risk of self inflicted downtime.

The role of managed hosting and managed VDS in reducing operational risk

Running a robust hosting stack involves more than paying for a server. As you add redundancy, monitoring and careful operations, the workload on your team grows.

Managed hosting and managed virtual dedicated servers can help when:

- Your in house team is small or wears many hats.

- The cost of downtime is high relative to the hosting bill.

- You want defined responsibilities and support around updates, monitoring and incident response.

With a managed service, you are effectively hiring a specialist operations team who live and breathe these concerns every day. You still retain control over your applications and business logic, but much of the infrastructure and maintenance burden is handled for you. If you are wondering whether this level of support is right for your stage, our article When Managed Hosting Makes Sense for Growing Businesses provides a structured way to think about it.

How to Compare Hosting Uptime Guarantees When Shortlisting Providers

Key questions to ask about uptime, failover and SLAs

When you speak with potential hosting providers, consider asking:

- What is the defined uptime target, and at what level of the stack is it measured?

- How is downtime detected and recorded for SLA purposes?

- What redundancy is built into the network, power, storage and compute layers?

- What options exist for high availability or failover for my use case?

- How are planned maintenance windows handled and communicated?

- What is the typical response time when an incident occurs?

The answers will usually tell you more about practical reliability than the percentage alone.

Checklist: what to look for in the SLA document itself

When reviewing the SLA document:

- Confirm the measurement period (per month, quarter or year).

- Note how short outages are treated.

- List the main exclusions and consider how likely they are for your environment.

- Check the compensation table and process, and whether it feels proportionate.

- See if there are different SLA tiers tied to specific architectures or managed services.

For more formal definitions of terms like “availability” and “reliability”, resources such as the ISO/IEC 23026 standard or classic works on site reliability engineering from major providers can provide deeper background, though they are more technical than most businesses need day to day.

Aligning your uptime expectations with your hosting model and budget

Finally, bring expectations, model and budget together:

- If your risk tolerance is low but budget is modest, focus on well designed single region architectures with good monitoring and managed elements.

- If your budget allows and risk is high, consider more advanced redundancy, potentially across facilities, with strong managed support.

- If risk is low, do not feel compelled to buy a complex setup you do not need simply because a higher percentage appears in the marketing material.

In some cases, moving from commodity shared hosting to carefully specified virtual machines or virtual dedicated servers for higher reliability and isolation can significantly improve real uptime without requiring public cloud scale or complexity.

Turning Uptime Guarantees Into a Practical Reliability Plan

Agreeing RTO and RPO internally before you buy hosting

Before choosing a provider, it helps to define two internal metrics:

- RTO (Recovery Time Objective): how long can the service be down before it causes unacceptable harm?

- RPO (Recovery Point Objective): how much data, measured in time, can you afford to lose? For example, is it acceptable to lose 10 minutes of transactions, or only a few seconds?

These figures do not need to be perfect, but they guide both your architecture choices and your expectations of any SLA. A provider can help you design for specific RTO and RPO targets, but it is your role to decide what those targets should be.

Documenting who does what during an incident

When an outage or serious incident occurs, clarity about roles and responsibilities is as important as the technology. Consider documenting:

- Who is authorised to contact the hosting provider and escalate issues.

- Who communicates with customers or internal stakeholders.

- Who makes decisions about rollbacks or failover activation.

- How decisions and timelines are recorded for later review.

This does not need to be a complex manual, but a simple, agreed plan helps avoid confusion when time matters.

When you have grown beyond shared hosting and need a more deliberate setup

Many organisations start on shared hosting, which is cost effective and simple. Signs that you may have outgrown it include:

- Frequent resource related slowdowns or timeouts.

- More intensive applications, such as busy WooCommerce or custom platforms.

- Stronger uptime expectations from management or clients.

- Compliance, security or separation requirements.

At this point, moving to a more deliberate architecture with dedicated or virtual dedicated resources, clearer SLAs and possibly managed support often makes sense. You do not need to jump directly to the most complex pattern, but you do benefit from treating hosting as part of your business continuity planning rather than a Commodity IT line item.

Summary: Realistic Uptime Is a Design Choice, Not a Marketing Slogan

Uptime guarantees are useful, but they are only one piece of the reliability puzzle. The real determinants of how often your site is down, and for how long, are:

- The architecture you choose: single server or high availability, redundancy and failover design.

- The quality of the underlying infrastructure: network, power, storage and data centre engineering.

- Your operational practices: monitoring, capacity planning, maintenance and change control.

- The clarity of responsibilities between you and your hosting provider.

Percentages on a sales page do not automatically translate into business outcomes. Translate those numbers into minutes and scenarios, weigh them against the cost of downtime for your organisation, and choose a level of complexity and managed support that you can realistically operate.

If you would like a pragmatic conversation about what level of uptime and architecture fits your specific situation, G7Cloud can help you weigh the options, from straightforward hosting to managed platforms and virtual dedicated servers, so you can make informed, low drama decisions about your next step.