Who This Comparison Is For (And The Decision You Need To Make)

Typical situations where this question comes up

You usually reach the “single data centre or multi‑site?” question when one of three things is happening:

- Your website or application has become important enough that outages now have a clear cost, in lost sales, lost leads or reputational damage.

- Someone senior has asked for “no downtime” or “disaster proof” hosting and you need to translate that into something realistic and affordable.

- A supplier, auditor or regulator has started asking about your resilience, uptime or disaster recovery arrangements.

If you run a WordPress brochure site, a busy WooCommerce shop, a booking system or a small SaaS product, all hosted in a single UK facility, you may be wondering:

- Is our current single data centre setup actually enough?

- Do we need a second data centre, region or cloud provider?

- What are we really protecting ourselves against, and at what cost?

What you should be able to decide by the end

By the end of this article you should be able to:

- Explain in plain English the difference between a strong single‑site setup and true multi‑site geographic redundancy.

- Understand the realistic failure risks for a well run data centre, and how often they matter for typical sites.

- Map downtime and data loss to business impact, using simple ideas like recovery time and recovery point.

- Decide whether multi‑site is a sensible investment for you now, something to plan for later, or unnecessary.

- Have a productive conversation with a provider about responsibilities, SLAs and managed versus unmanaged options.

The aim is not to push you towards a particular architecture, but to help you make a decision that fits your budget, your risk appetite and your operational capacity.

Plain English Basics: What Single Data Centre and Multi‑Site Really Mean

Single data centre hosting in practice

“Single data centre” simply means all of your live hosting is in one physical building or campus, run by one provider. Within that building there can still be a lot of redundancy:

- Multiple power feeds, UPS and generators.

- Redundant cooling systems.

- Several internet uplinks and network paths.

- Clusters of servers, rather than one lone machine.

So single data centre does not automatically mean fragile. A well designed single‑site setup can ride out many faults without noticeable downtime.

For example, a WordPress site running on a cluster of virtual dedicated servers in one data centre can survive individual server failures, network switch problems and local power incidents within that facility.

Multi‑site and geographic redundancy in practice

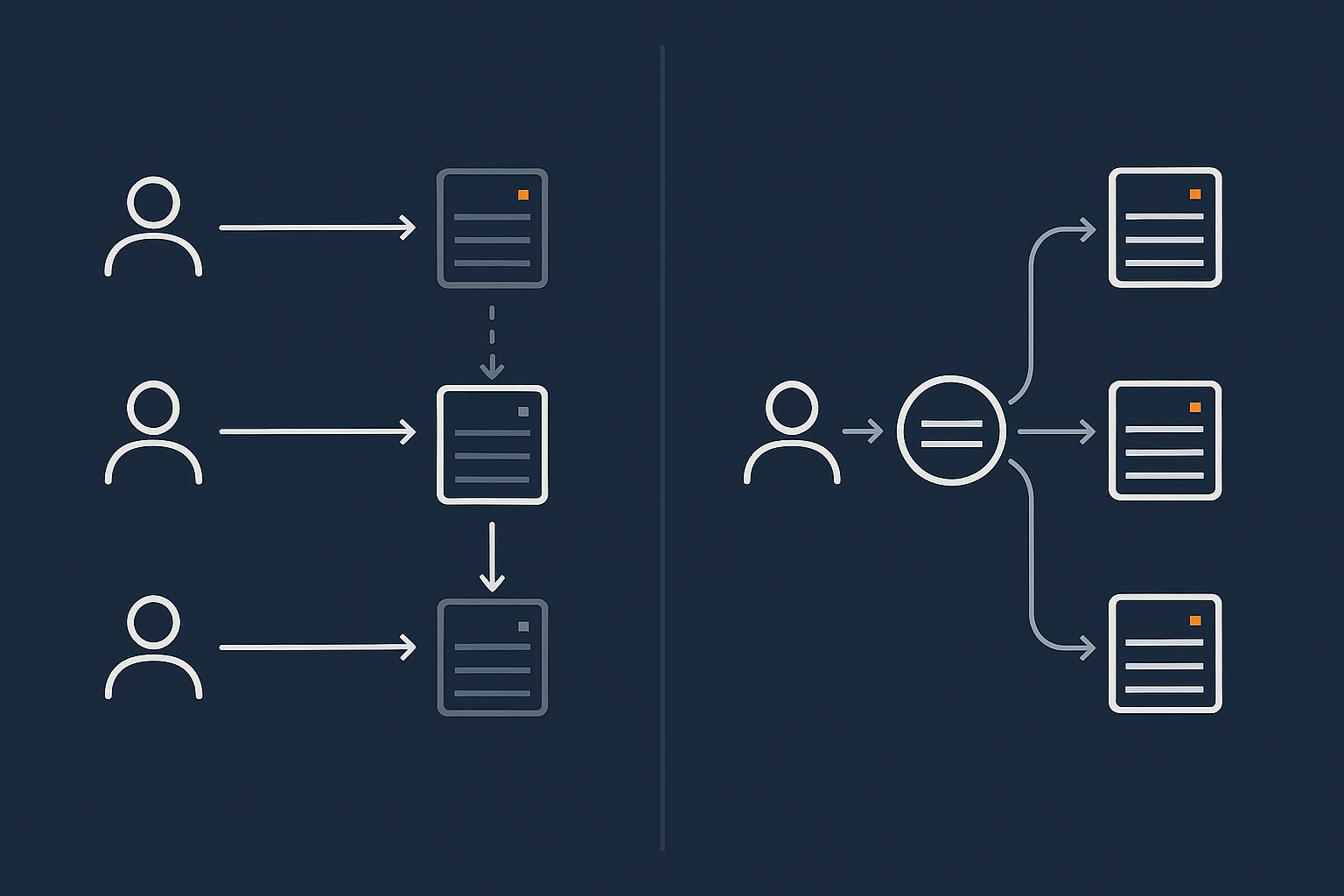

“Multi‑site” or “geographically redundant” hosting means you have two or more separate locations that can in some way take over for each other. The degree of redundancy varies:

- Active‑passive where one site serves all traffic, and another is on standby.

- Active‑active where two or more sites share traffic all the time.

- Cold standby where a second site can be brought online from backups, but is not kept fully ready.

The core idea is simple: if something happens to one location, another can keep you running, or at least get you back online much faster than rebuilding from scratch.

How this relates to uptime, SLAs and “high availability”

Terminology in this area can be confusing:

- Uptime is normally expressed as a percentage per month or year, such as 99.9%.

- SLAs (Service Level Agreements) are contractual promises about uptime and response, often with credits if targets are not met.

- High availability describes architectures that avoid single points of failure, usually through clustering, load balancing and redundancy.

High availability can exist in a single data centre or across several. A multi‑site architecture does not automatically mean you have a better SLA. And a strong SLA does not mean there is no risk of downtime, as discussed in “Five Nines” and Other Myths: How to Realistically Evaluate Hosting Uptime Guarantees.

In practice, most providers structure SLAs around their own infrastructure. Geographic redundancy, if you choose it, usually needs to be designed specifically for your application.

What Can Actually Go Wrong In A Single Data Centre?

Common, local failures that good data centres already handle (power, cooling, single links)

A modern data centre is built to cope with many everyday failures:

- Power issues: multiple feeds, battery backup and generators handle grid problems.

- Cooling problems: N+1 or better cooling designs mean one unit can fail without overheating the room.

- Individual network link failures: multiple uplinks and routers keep connectivity even if one path is lost.

- Hardware faults: failed disks, power supplies or even whole servers are expected and designed for.

If your architecture inside that data centre also uses redundancy, many of these incidents will not take your site offline at all, or will only cause brief disruption. Clustering, load balancing and storage redundancy handle the majority of day‑to‑day risks.

Rarer, building‑level incidents (fire, flooding, major power issues)

The scenarios that normally drive multi‑site discussions are less frequent but higher impact:

- Fire affecting an entire data hall or building.

- Major flooding or structural damage.

- Prolonged total loss of power or cooling.

- Serious security incident that requires shutting the facility down.

These events are rare in well operated UK and EU facilities, but they are not impossible. When they do occur, recovery time is often measured in many hours or days, which may not fit your risk tolerance if the site is critical to revenue or compliance.

Upstream and internet routing incidents (when the building is fine but you are still offline)

Sometimes the building is perfectly healthy but your services are still unreachable due to:

- Major routing problems with an upstream carrier.

- Significant DDoS attacks saturating links.

- Fibre cuts that knock out several providers along the same route.

Good providers design multiple physical paths and work with several carriers to reduce this risk. Some use traffic filtering and scrubbing to handle hostile traffic. The G7 Acceleration Network, for example, can filter abusive traffic and cache content at the edge, which reduces pressure on the core data centre during internet routing incidents.

How often these risks matter for typical WordPress and WooCommerce sites

For most brochure WordPress sites and many WooCommerce shops focused on a single market, the chance of a catastrophic building‑level incident during any given year is low, particularly in reputable UK or EU facilities.

The more common causes of downtime are usually:

- Application updates breaking the site.

- Plugin or theme conflicts.

- Traffic spikes overloading under‑sized servers.

- Misconfigurations and deployment mistakes.

These are problems geographic redundancy does not solve by itself. If you replicate a broken application setup into two data centres, it can break in both places at once.

Single Site vs Multi‑Site: What Problem Are You Actually Trying To Solve?

Distinguishing performance, uptime, resilience and disaster recovery

It helps to separate a few related but different goals:

- Performance: how fast the site feels to users.

- Uptime: how often the site is reachable and functioning.

- Resilience: how well the system copes with incidents without serious disruption.

- Disaster recovery: how quickly you can restore service after a major failure.

A second data centre mainly helps with resilience and disaster recovery. Performance for users in other countries is usually better addressed with edge caching and a content delivery network, such as the G7 Acceleration Network, which can cache content closer to users and optimise images to modern formats like AVIF and WebP on the fly.

Backups vs redundancy vs disaster recovery: what each one really covers

These three concepts are often mixed up:

- Backups are copies of data you can restore from if something is deleted or corrupted.

- Redundancy is additional capacity or components that keep systems running when something fails.

- Disaster recovery is the process and tooling to rebuild or switch services after a major incident.

If you want a deeper dive into this distinction, see Backups vs Redundancy: What Actually Protects Your Website.

How geographic redundancy fits into an overall resilience plan

Geographic redundancy is one layer in a broader strategy:

- Inside the data centre: resilience against common hardware and network faults.

- Across data centres: the ability to switch or rebuild if a whole site is lost.

- Operationally: sensible change control, monitoring, and tested recovery procedures.

It makes little sense to invest heavily in multi‑site architecture if you do not yet have reliable backups, basic monitoring and a clear recovery plan. Those more modest steps often deliver a much better return for typical small and mid‑sized organisations.

When A Single Well‑Engineered Data Centre Is Usually Enough

Business profiles that are fine with a robust single‑site setup

In many cases, a solid single‑data‑centre design is entirely appropriate. Typical examples include:

- Brochure and content sites, where brief outages are inconvenient but not critical.

- Lead generation sites where leads can be captured again later without major loss.

- Most UK focused WooCommerce shops doing moderate turnover.

- Internal tools with clear workarounds if the system is briefly unavailable.

If the direct financial impact of a one or two hour outage is low, and there are no strict regulatory uptime requirements, then the extra complexity and cost of multi‑site is often hard to justify.

What “strong single site” should include (inside the building)

Power, cooling and network redundancy in one facility

Your provider should be able to describe:

- How power is fed into the facility and backed up.

- How cooling is designed to tolerate failures.

- How many distinct network carriers they use.

Look for a clear explanation of how they cope with common incidents, not just marketing terms.

Server‑level redundancy and failover within the data centre

Within the data centre itself, a strong single‑site design typically uses:

- Clusters of servers rather than a single machine.

- Load balancers to distribute web traffic.

- Redundant storage or database replication within the site.

For example, your WordPress or WooCommerce site might run across a small cluster of virtual dedicated servers that can tolerate a node failure without taking the site offline.

Off‑site backups and realistic recovery times

Even with internal redundancy, you still need backups. At a minimum:

- Regular, automated backups of files and databases.

- Copies stored off‑site or in a different region.

- Tested restore procedures and clear recovery times.

This is where disaster recovery overlaps with geographic considerations. You may not need a fully live second data centre, but you do want your backups stored away from the primary facility, and a plan for how to use them.

Realistic examples: brochure WordPress, lead gen, most UK WooCommerce stores

For a UK based small business with:

- Turnover that does not rely on 24/7 online sales.

- A local customer base.

- No strict regulatory uptime requirements.

A strong single data centre plus good backups and a sensible disaster recovery plan is usually a practical “sweet spot”. Multi‑site may still be something to consider later, but it does not need to be the first step.

When Multi‑Site or Geographic Redundancy Starts To Make Sense

Business and regulatory drivers (not just technical enthusiasm)

Multi‑site setups are most often justified by:

- High financial exposure: where even short outages translate directly to significant lost revenue.

- Regulatory requirements: for example, some financial or healthcare contexts expect documented business continuity and secondary sites.

- Contractual SLAs you offer to your own customers that commit you to specific uptime or recovery times.

- Reputational sensitivity: where availability is closely tied to brand trust.

Concrete scenarios where dual data centres or regions are justified

Examples where multi‑site often makes sense:

- A busy online retailer where each minute of downtime during peak trading has a measurable cost.

- A B2B SaaS platform with customers across time zones and contractually agreed SLAs.

- An online system that supports critical operations, such as logistics or healthcare scheduling.

- Organisations required to meet formal business continuity standards, such as ISO 22301.

In these situations, a second data centre provides a meaningful reduction in the risk of long outages due to facility‑level incidents or major network problems.

How this interacts with PCI, SLAs and contractual obligations

If you handle card payments or other regulated data, you may already be thinking about PCI conscious hosting and similar frameworks. Multi‑site can help demonstrate that:

- You have considered business continuity and disaster recovery.

- You can continue to process transactions or restore service within defined windows.

Similarly, if your contracts promise specific recovery times or uptime levels, you need an architecture that makes those commitments realistic rather than aspirational.

Multi‑Site Architectures in Plain English: Options And Trade‑Offs

Active‑passive: primary site with warm or cold standby

How failover works (DNS, IP failover, replication)

In an active‑passive design, one site serves all traffic. The second site is there to take over if needed.

There are a few common patterns:

- Cold standby: backups are stored off‑site and, in a disaster, you rebuild onto infrastructure in another location. This can take hours or longer.

- Warm standby: systems are running in the second site, receiving regular data replication, but not serving traffic. Failover is faster, often using DNS changes or IP failover.

DNS based failover changes where your domain points. IP failover moves a routable IP block between data centres. Both require careful planning, health checks and testing.

Pros, cons and suitable use cases

Active‑passive offers:

- Lower cost than active‑active because only one site is handling live traffic.

- Clear separation between primary and secondary environments.

- Reasonable recovery times for many businesses.

The trade offs include:

- More complex operations than single‑site.

- A risk of configuration drift if the standby is not maintained properly.

- The need to rehearse failover so that the process is predictable.

Active‑active: live in two data centres at once

Load balancing and data consistency basics

In an active‑active design, two or more sites all serve traffic at the same time. Load balancing spreads users across them. The main challenge is keeping data consistent.

For read heavy workloads, such as content sites, this is relatively straightforward if you centralise or carefully replicate the data store. For write heavy systems like transactional e‑commerce, it becomes more involved and may require database technologies specifically designed for multi‑region operation.

Why complexity and cost rise quickly

Active‑active designs:

- Double the amount of live infrastructure you manage.

- Require more sophisticated monitoring and observability.

- Need careful thinking about data integrity, conflict resolution and deployments.

They can deliver excellent resilience and performance for global audiences, but they are rarely the first step for small and mid‑sized organisations. Managed services can help here, because the operational load is considerable for a small in‑house team.

Global performance vs true geographic redundancy (CDN, edge caching, G7 Acceleration Network)

It is important not to confuse multi‑site hosting with global performance optimisation:

- A CDN or edge network improves performance worldwide by caching content near users.

- Geographic redundancy keeps your core application available if one site fails.

The G7 Acceleration Network sits in front of origin servers, caching pages, filtering abusive traffic and converting images to AVIF or WebP, often cutting image weight by more than 60 percent. This makes single‑site hosting feel significantly faster for distant users, but it does not replace the need for a second data centre if your risk profile truly requires it.

Key Design Questions: How To Decide What Level Of Redundancy You Need

Step 1: Map real business impact of downtime and data loss (RTO, RPO in plain English)

Two useful concepts help clarify requirements:

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO): how quickly you need to be back online after an incident.

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO): how much data you can afford to lose, measured as time since the last good copy.

You do not need to use the jargon internally. You can ask:

- “If the site vanished at 2pm on Tuesday, by when would this start to be really painful?”

- “If we had to restore from a backup from 3 hours ago, is that acceptable? What about yesterday?”

The answers will tell you whether you need minutes, hours or days of recovery, and how frequently you should be capturing data.

Step 2: Identify realistic risks for your location and platform

Next, look at your context:

- Where is your data centre located?

- What is the provider’s track record and certification?

- Are there known local risks such as flooding?

- How complex is your application stack?

This gives you a grounded view of likely incidents, so you can design for realistic scenarios rather than only for theoretical extremes.

Step 3: Match architecture to risk, not worst‑case imagination

If the real impact of a data centre wide event is low for your business, and your RTO can be measured in hours or days, then a combination of strong single‑site design plus robust off‑site backups is often enough.

If a long outage would be genuinely damaging, and your RTO is short, then investing in multi‑site starts to look more reasonable. The aim is not to eliminate all possible risk, but to bring it to a level that matches your priorities and budget.

Step 4: Clarify who does what with your provider (managed vs unmanaged responsibilities)

A hosting provider can:

- Design and run reliable infrastructure across one or more data centres.

- Provide tools for backups, replication and monitoring.

- Offer managed services to handle much of the operational work.

You, or your technical partners, are still responsible for:

- Defining acceptable downtime and data loss.

- Deciding which parts of your system are critical.

- Testing application‑level failover and recovery.

If your in‑house capacity is limited and the system is important, managed hosting or managed virtual dedicated servers can reduce operational risk, because the provider takes on more of the day‑to‑day management and incident response.

Common Mistakes With Geographic Redundancy (And How To Avoid Them)

Confusing CDN or caching with multi‑data‑centre resilience

A CDN or edge network improves speed and can shield your origin from some traffic surges, but if the core application in the data centre is unavailable, there are limits to what caching can do, especially for dynamic sites like WooCommerce stores.

Do not assume that “we have a CDN, so we are redundant”. They solve different problems.

Over‑engineering for a brochure site, under‑engineering for payments

It is surprisingly common to see:

- Simple brochure sites built on complex, costly multi‑region stacks they do not need.

- Busy payment‑taking sites still on a single unmanaged VPS with no off‑site backups.

Matching architecture to actual risk, as described earlier, avoids both extremes.

Relying on untested failover or single‑site backups stored in the same facility

Two specific issues to avoid:

- Failover mechanisms that have never been rehearsed in a realistic test.

- Backups stored only in the same data centre, which does not help in a facility‑wide incident.

Periodic recovery drills and storing backups in a different location are cost‑effective improvements compared with jumping straight to a fully live second site.

Ignoring DNS, payment gateways and third parties in the overall chain

Your resilience depends on more than just your hosting:

- DNS providers can fail or be attacked.

- Payment gateways can have outages.

- Third‑party APIs you rely on can go down.

A realistic plan looks at the full chain. For example, you might choose DNS providers with good track records, and accept that card payments may occasionally be disrupted even if your own hosting remains healthy.

Practical Next Steps: From Single Site Today To Sensible Resilience Over Time

If you are on shared or basic managed hosting today

Practical first steps:

- Confirm there are regular, off‑site backups and understand how restores work.

- Ask about the provider’s web hosting security features and incident history.

- Consider moving critical sites to a more isolated environment, such as a managed VPS or virtual dedicated server, where resources and configuration are under clearer control.

You may find that these changes, plus a sensible disaster recovery plan, give you all the resilience you realistically need for now.

If you are already on a VPS or virtual dedicated server

If you already have your own VPS or cluster:

- Check that backups are both frequent enough and stored off‑site.

- Review server‑level redundancy and failover within the data centre.

- Introduce basic monitoring and alerting so you know when something is wrong.

At this level, you can start to explore simple active‑passive designs or documented rebuild plans, often with support from your provider. Managed services become attractive here because mistakes with replication or failover can cause data inconsistency or extended downtime.

How to talk about geographic redundancy with a hosting provider

When you speak to a provider, you do not need to specify every technical detail. Instead, explain:

- How critical each system is to your business.

- Acceptable outage durations and data loss windows.

- Any regulatory or contractual commitments you have made.

A good provider can then suggest appropriate architectures, perhaps drawing on patterns described in Designing for Resilience: Practical Redundancy and Failover When You Are Not on Public Cloud.

Where enterprise and PCI‑conscious hosting fits into this picture

If you are handling payments at scale, regulated data or complex multi‑site architectures, enterprise grade or PCI conscious hosting becomes relevant. These services typically:

- Provide support for multi‑site and high availability designs.

- Help align infrastructure with regulatory expectations.

- Offer managed operations so that your internal team is not carrying all of the burden.

They are not necessary for every organisation, but they are worth exploring when the risk and complexity justify the investment.

Summary: A Simple Rule‑Of‑Thumb For Single vs Multi‑Site Hosting

Most small and mid‑sized organisations get good value from:

- A well designed single data centre architecture with internal redundancy.

- Regular, tested, off‑site backups.

- A realistic disaster recovery plan and clear responsibilities.

Multi‑site hosting becomes a sensible option when:

- The cost of a long outage is high and immediate.

- You have strict uptime or recovery commitments.

- You are operating under regulatory frameworks that expect documented geographic redundancy.

Checklist you can use internally to justify your choice

You can use the following checklist in internal discussions:

- What is the real business impact of 1 hour, 4 hours, 24 hours of downtime?

- How much data could we afford to lose: minutes, hours, a day?

- Do we already have strong single‑site resilience (power, network, server redundancy)?

- Are backups frequent, off‑site and regularly tested?

- Do we have regulatory or contractual obligations that suggest multi‑site?

- Do we have the in‑house capacity to run multi‑site, or would we need managed services?

- Is global performance our main goal, or true geographic redundancy?

If you can answer these questions clearly, you will be in a strong position to justify either sticking with a robust single data centre approach or investing in multi‑site hosting.

If you would like a second opinion on your specific situation, you are welcome to speak with G7Cloud about single‑site, multi‑site and managed virtual dedicated servers, so you can choose a hosting architecture that fits your risks without unnecessary complexity.