Inside a Data Centre: What Really Matters for Power, Cooling and Network Redundancy

Who This Guide Is For (And Why the Data Centre Itself Matters)

When infrastructure stops being a detail

If your website or application has become central to how you earn money or serve customers, the building it runs in is no longer a background detail.

You might be:

- Running a busy WordPress or WooCommerce site where an outage during trading hours means lost orders.

- Hosting client sites and carrying the blame if they go down.

- Operating internal systems that staff rely on to do their jobs every day.

At that point, terms like “Tier III”, “dual power feeds” or “N+1 cooling” start appearing in proposals and sales calls. They clearly sound important, but they can also feel like jargon designed to push you into more expensive options.

The purpose of this guide is to give you enough understanding of data centre power, cooling and network redundancy to:

- Recognise what is genuinely improving reliability and what is mostly marketing gloss.

- Match the level of resilience to how critical your systems are.

- Decide when managing the risk yourself is reasonable and when to consider a managed approach.

What you will be able to judge by the end

By the end of this article you should be comfortable judging:

- What “redundancy” really is, and how it differs from backups and SLAs.

- How data centre infrastructure supports uptime guarantees, and where your own hosting architecture must take over.

- The real meaning of terms like N, N+1, 2N and Tier III / Tier IV.

- What sensible questions to ask a provider about power, cooling and networking.

- When a simple setup is enough and when you should be thinking about more resilient designs or virtual dedicated servers.

This is not about turning you into a facilities engineer. It is about making better, calmer decisions with your budget and risk in mind.

Plain‑English Building Blocks: Power, Cooling, Network and Redundancy

What redundancy actually means, separate from backups and SLAs

Redundancy means having at least one independent alternative ready to take over if something fails, without a lengthy interruption.

Typical examples in a data centre are:

- Two separate power feeds to a rack. If one fails, the servers remain on.

- Extra cooling capacity so a failed unit does not overheat the room.

- Multiple network carriers and paths, so a fibre cut does not take you offline.

Redundancy is not the same as:

- Backups which protect your data if it is lost or corrupted.

- SLAs which are contractual promises about uptime or response times.

The article “Backups vs Redundancy: What Actually Protects Your Website” goes deeper into the difference between these.

You can have excellent redundancy and poor backups, or excellent backups and very little redundancy. Reliable services usually need both.

How data centre infrastructure underpins uptime guarantees

When you see an uptime figure such as “99.9%”, part of that is achieved through software, monitoring and processes. Another part rests entirely on the physical infrastructure:

- Resilient power keeps servers running during grid problems.

- Resilient cooling prevents heat shutdowns.

- Resilient networking keeps packets flowing in and out.

If any of those is fragile, there is a hard limit to the uptime a hosting provider can realistically deliver, no matter which platform they use.

For a deeper look at uptime figures and what they mean in practice, you may find “Five Nines and Other Myths: How to Realistically Evaluate Hosting Uptime Guarantees” useful after this article.

Tiers, ratings and jargon you might hear (N, N+1, 2N, Tier III/IV etc)

A few terms are worth clarifying at the outset:

- N is the amount of capacity you need to run normally. For example, if you need 4 cooling units to keep temperatures in range, N = 4.

- N+1 means you have one extra unit beyond what you strictly need. If you need 4, you have 5.

- 2N means you have a complete duplicate system. For example, two entirely separate power systems, each able to handle the full load on its own.

On top of that, you may hear about “Tier III” or “Tier IV” data centres. These refer to a classification from the Uptime Institute that looks at redundancy and maintainability. Their tier definitions explain this in formal terms, but in broad strokes:

- Tier III facilities are “concurrently maintainable”. You can take key components out of service for maintenance without shutting everything down. They usually involve N+1 redundancy on core systems.

- Tier IV facilities add “fault tolerance”, often with 2N or even more complex designs.

You do not need to chase the highest possible tier. The right level depends on how critical your workloads are and how much unplanned downtime your business can tolerate.

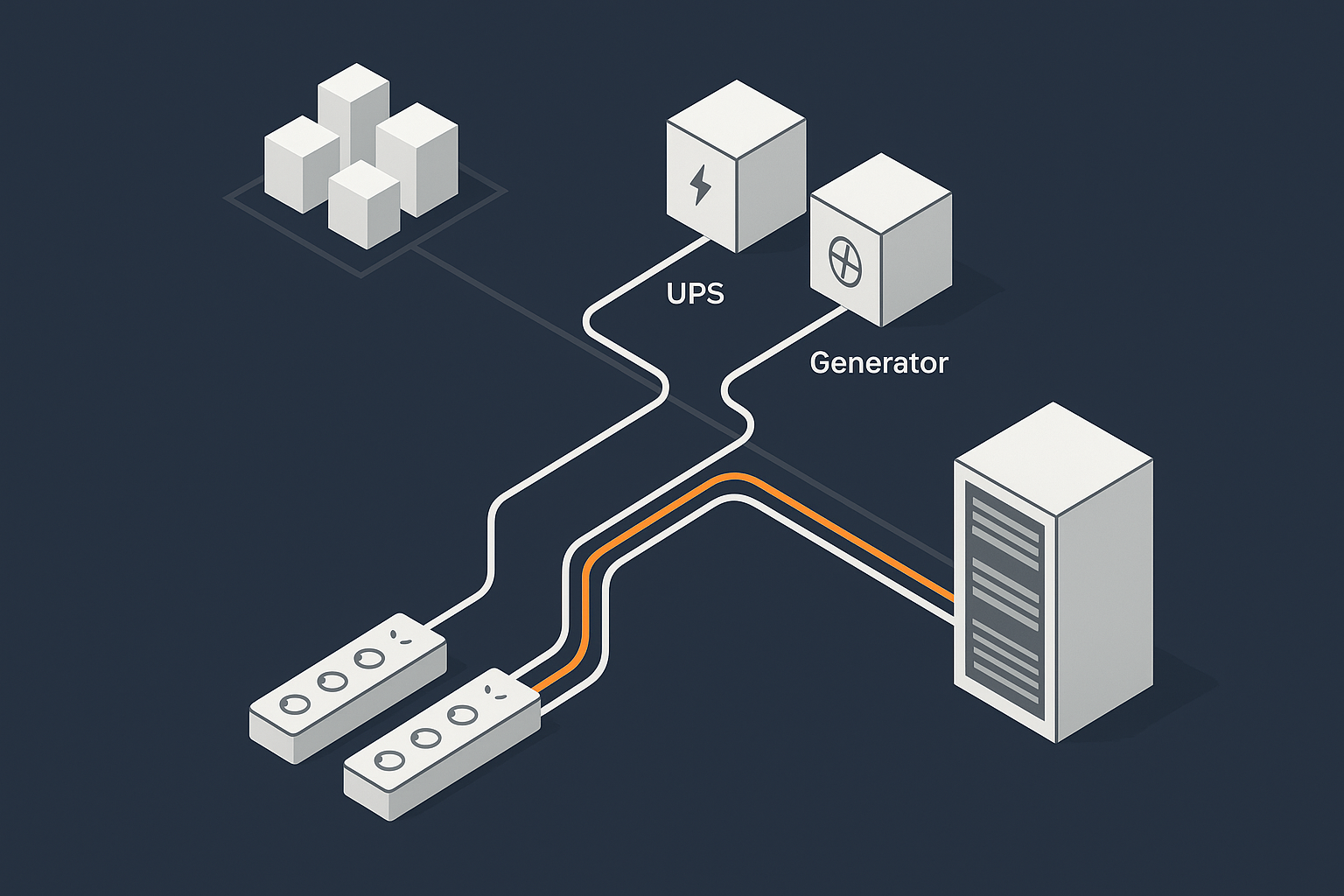

Power Redundancy: Keeping Servers On When the Lights Go Out

Where power comes from in a typical data centre

Power in a well designed data centre usually flows in stages:

- One or more feeds from the national grid, often from different substations.

- Switchgear that can move the load between feeds.

- Uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) that bridge the gap during issues.

- Generators that provide longer term backup if the grid is unavailable.

- Power distribution units (PDUs) delivering electricity to racks and servers.

The aim is not to avoid all grid problems, which are outside anyone’s control, but to avoid those problems reaching your servers.

UPS systems: buying time for a clean handover

A UPS is essentially a big battery system combined with electronics that smooth and condition power. It provides:

- Instant response when grid power dips or disappears.

- Clean power by ironing out minor fluctuations and spikes.

Typical UPS systems provide enough energy for anything from a few minutes up to perhaps an hour, depending on design. That is usually enough time for generators to start and take over the load, or for an alternative power feed to be brought online.

Without a UPS, a power cut often means servers drop instantly, increasing the risk of data corruption as well as downtime.

Generators, fuel and realistic failover times

Generators are the muscle behind long term resilience. Key aspects include:

- Start time. Generators do not start instantly, so the UPS carries the load until they are up to speed.

- Run time. How long they can run is determined by fuel storage and the ability to refuel during an extended outage.

- Testing. Regular, realistic load testing is essential. Quietly spinning a generator on no load tells you far less than testing a real switch to generator power.

A mature data centre design will treat “grid goes off, generator comes on” as a routine event, not a crisis. That makes a significant difference to how often things go wrong when power issues occur.

Dual power feeds, PDUs and avoiding single points of failure

A resilient building level power system is important, but it only helps if power is also delivered to your equipment in a resilient way.

Common patterns include:

- Dual power feeds to each rack. Each feed connects to a different UPS and generator path.

- Dual PDUs in the rack. So a failed PDU or circuit breaker does not cut all power to your servers.

- Servers with dual power supplies. Each power supply plugs into a different PDU, so a single failure does not stop the server.

Here you start to see the join between data centre design and your own hosting architecture. If your servers only have one power supply or are all on one PDU, some of the building level redundancy cannot protect you fully.

Questions to ask a provider about power design and testing

Questions that usually produce useful, concrete answers include:

- “Is the facility designed with N+1 or 2N power for the critical systems?”

- “Do racks have dual power feeds from separate UPS systems, and can each support the full rack load?”

- “How often do you test generator failovers under live or realistic load?”

- “During planned power maintenance, is each rack expected to stay online, or is downtime possible?”

- “What protections are in place against overloading a power circuit in my rack?”

Look for answers that mention specific designs and test routines, rather than only quoting high level SLAs.

Common myths and weak spots in power redundancy

A few recurring issues to be aware of:

- “Generator present” does not equal “properly tested failsafe”. Ask about test procedures and past experience.

- Dual grid feeds that share critical components. If both feeds rely on the same transformer or switchgear, a single failure can still take everything down.

- Overloaded racks. Even in a good building, if too many high draw servers are crammed onto one power circuit, local trips can cause downtime.

These are reasons to ask detailed questions, not reasons to be anxious. A provider that is open about past issues and how they were fixed is often more reliable in the long run than one that insists nothing ever goes wrong.

Cooling Redundancy: Why Temperature Control Is an Uptime Issue, Not a Comfort Issue

How servers are cooled in practice (rows, hot and cold aisles, CRAC/CRAH units)

Servers are essentially sophisticated electric heaters. Almost all the power they consume becomes heat that must be removed.

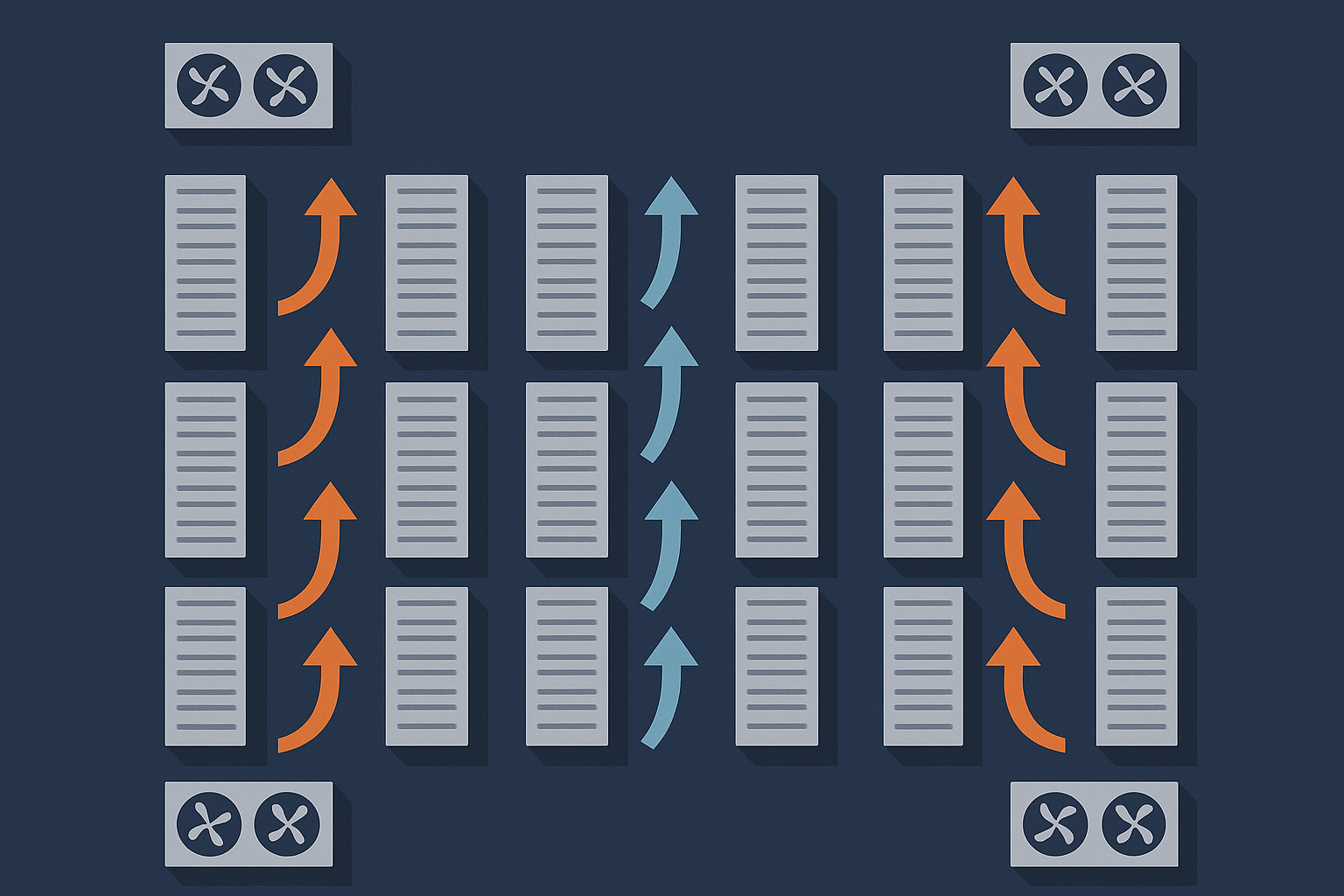

Most data centres use some variation of:

- Rows of racks arranged to form “cold aisles” at the front and “hot aisles” at the back.

- Cold air blown into the cold aisles, pulled through the servers and exhausted as hot air into the hot aisles.

- CRAC / CRAH units (Computer Room Air Conditioning / Handling) that chill and circulate the air or water used for cooling.

The crucial point is that cooling is part of keeping systems running safely, not a comfort feature. If cooling fails, servers can reach critical temperatures in minutes, especially under load.

What N+1 and 2N cooling really look like

In cooling, N+1 and 2N patterns are broadly similar to power:

- N+1 cooling means there is at least one extra cooling unit beyond what is needed for the expected load. If one fails, the remaining units can still maintain acceptable temperatures.

- 2N cooling might mean two entirely separate cooling systems serving the same room, often with independent pipework and power feeds.

Many modern facilities use N+1 cooling, with some areas or higher tier sections moving towards 2N designs as densities and critical workloads increase.

Environmental monitoring: temperature, humidity and alerts

Redundancy is only useful if the team knows when something is drifting out of normal range.

Well run data centres will have:

- Temperature and humidity sensors spread around the room, not just at one point.

- Thresholds for warnings and alarms when values move towards unsafe levels.

- Procedures for responding to environmental alerts quickly, before equipment is at risk.

On a smaller scale, hosting teams may add their own temperature sensors in critical racks to give additional visibility.

Failure modes: what actually happens when cooling is lost

Cooling problems tend to unfold in stages:

- A cooling unit or chiller fails, or airflow is obstructed.

- Temperatures begin to rise, sometimes in certain aisles first.

- Servers may start to throttle performance as internal safeguards try to protect components.

- If temperatures rise too far, servers shut down to avoid hardware damage.

In a resilient design, either redundant cooling units take over or staff have time to shift loads, adjust airflow or move services before shutdowns occur.

Questions to ask a provider about cooling capacity and resilience

Helpful questions include:

- “Is the cooling system designed to N+1 or 2N, and at what load level?”

- “How do you monitor temperatures across the data hall, and what are your alert thresholds?”

- “What is your process if a cooling failure occurs while the room is near capacity?”

- “Do you have any limitations on rack power density that might affect future growth?”

These questions are less about interrogating the exact HVAC design and more about understanding whether the facility has thought about heat as a first class reliability concern.

Network Redundancy: Multiple Paths In and Out of the Data Centre

How traffic gets from your visitors to your rack

At a high level, network traffic usually travels:

- From the visitor’s ISP into one or more backbone networks.

- Across those networks to one of the carriers that has a presence in the data centre.

- Through fibre lines into the building and onto core routers and switches.

- From the core into aggregation switches, then to your rack and servers.

At each step, there are potential points of failure. Network redundancy aims to give each step at least one alternative path.

Carrier diversity, diverse paths and why “dual fibre” is not always enough

Having “dual fibre” or “two carriers” sounds reassuring, but the detail matters.

Important concepts include:

- Carrier diversity. Using multiple independent carriers, so that a problem within one provider’s network does not affect you completely.

- Path diversity. Ensuring fibres use genuinely different physical routes. Two cables in the same duct are vulnerable to the same digger.

- Diverse entry points. Cables entering the building through different physical points, reducing the impact of a localised incident near one entry.

When a provider says they have diverse carriers and routes, it is reasonable to ask for a plain language description of what that looks like.

Routers, switches and redundant core network design

Inside the data centre, routers and switches form the spine of connectivity.

A resilient internal network might include:

- Redundant core routers that can each carry the full load, often arranged in “active / active” designs.

- Redundant links between core and distribution switches, usually configured with protocols that can automatically route around failures.

- Dual uplinks per rack, with servers connected to separate switches where possible.

Just as with power, building level redundancy only helps you fully if your own equipment connects to it in a resilient way.

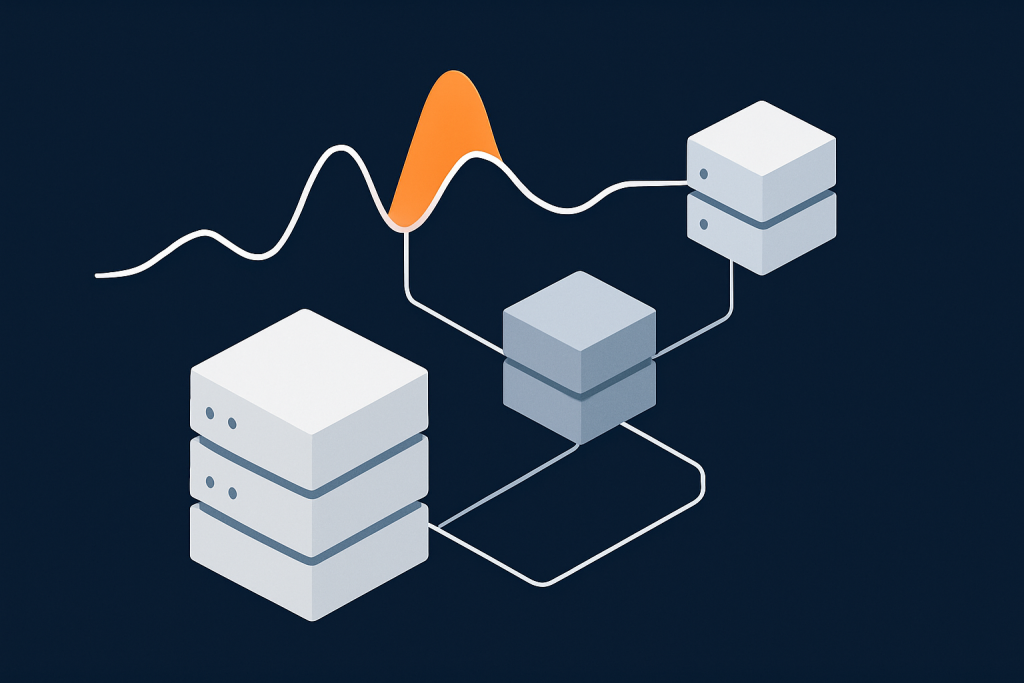

DDoS protection, bad bot filtering and edge optimisation

Not all network problems are accidental. Volumetric attacks or abusive traffic can also affect availability and performance.

Some providers operate protection at or near the “edge” of their network, before traffic hits your servers. For example, the G7 Acceleration Network caches static content, optimises images to AVIF and WebP on the fly, and filters abusive traffic before it reaches application servers. This can both reduce load on your infrastructure and help maintain availability during traffic spikes.

Capabilities like this sit on top of basic physical redundancy. They do not replace having multiple carriers and resilient routing, but they can significantly improve real world uptime and performance, especially for public facing sites.

Key questions to ask about network redundancy and capacity

Useful questions to explore with a provider:

- “Which carriers do you connect to, and are there diverse paths into the building?”

- “How is the core network designed for redundancy? Can any single device failure interrupt service?”

- “What capacity headroom do you maintain under normal conditions?”

- “What forms of DDoS mitigation or bad traffic filtering are in place before traffic reaches my servers?”

Look for answers that describe concrete capacity planning and redundancy approaches rather than just peak theoretical bandwidth figures.

Redundancy Levels: From Single Server to Highly Available Setups

What the data centre gives you by default vs what your hosting architecture must do

A well designed data centre can give you:

- Resilient power, cooling and connectivity at the building level.

- Physical security and environmental monitoring.

- Skilled engineers to operate that infrastructure.

What it cannot do on its own is:

- Prevent downtime if your single server fails or needs maintenance.

- Automatically scale your application during traffic spikes.

- Guarantee recovery from software bugs, configuration mistakes or data corruption.

Those aspects depend on your hosting architecture and operational practices. The article “Single Server vs Multi Server Architecture: How to Decide When You Are Not on Public Cloud” looks at these choices in more depth.

Single server, clustered and multi‑server designs in a redundant facility

Inside the same resilient facility, you might choose:

- Single server. Simple and cost effective, but any hardware or OS failure means downtime while you repair or restore elsewhere.

- Active / passive pair. Two servers, with a primary handling traffic and a secondary ready to take over if the primary fails.

- Clustered / multi server. Several servers share load. If one fails, others continue serving traffic. This is common for higher traffic sites and databases.

All of these benefit from the data centre’s physical redundancy but they have very different risk and complexity profiles. Running multi server clusters introduces configuration and failover challenges that smaller in house teams may find demanding, which is where managed services can be useful.

How this relates to shared hosting, VPS and virtual dedicated servers

Different hosting models give you different levels of control over redundancy:

- Shared hosting places many sites on the same physical servers. You benefit from the provider’s redundancy decisions, but have limited control and isolation.

- VPS (Virtual Private Servers) give you more dedicated resources and customisation, but usually still share hardware and some failure domains with others.

- Virtual dedicated servers provide isolated, high performance resources that behave more like your own servers, often with clearer options for building redundancy at the server and application level.

As the importance of your workloads grows, moving from basic shared hosting to VPS or VDS often makes sense, not because the building changes, but because your ability to control redundancy and risk improves.

When you might need cross‑data‑centre redundancy

Even the best single data centre is still a single physical location. If:

- Your application is business critical, and even rare regional outages are unacceptable.

- You have regulatory or internal requirements for disaster recovery in a separate location.

- You serve users across wide geographies and want lower latency in multiple regions.

then it can be worth looking at hosting architectures that span multiple data centres.

This brings additional cost and complexity around data replication, failover logic and testing. It is often an area where partnering with a provider that offers managed multi site designs is preferable to building everything in house.

“Designing for Resilience: Practical Redundancy and Failover When You Are Not on Public Cloud” explores some of these approaches.

Testing, Maintenance and Human Factors: The Side of Redundancy You Cannot See

Planned power tests and live failover drills

Infrastructure that looks good on paper still needs to prove itself in real conditions. Mature operators will periodically:

- Run power failover tests where they deliberately transfer load to generators.

- Test the switchover between network paths or core devices.

- Validate that monitoring and alarms behave as expected during these events.

These tests are usually planned and communicated in advance, and should be carried out in a way that keeps customer services online. Asking a provider about their testing regime can tell you a lot about how confident they really are in their design.

Maintenance windows, change control and communication

Even in redundant systems, changes can introduce risk. Good practice includes:

- Defined maintenance windows where non urgent changes are made.

- Change control processes that assess the risk of each change in advance.

- Clear communication with customers about work that could affect them.

For your own part, it is wise to align major application changes with hosting provider maintenance windows where possible, so that you do not stack risks inadvertently.

Monitoring, alarms and on‑site engineers

Beyond the physical design, reliability depends on people and processes:

- Comprehensive monitoring of power, cooling, security and network systems.

- Alarm thresholds tuned to catch issues early, without overwhelming staff with noise.

- Trained engineers on site or on call 24/7 with the authority to act quickly.

When you are evaluating providers, ask whether there are engineers physically present on site around the clock, and how incident escalation works in practice.

How Data Centre Design Ties Into Compliance and Risk (Including PCI‑Conscious Hosting)

Physical security and access control basics

For many organisations, part of the risk calculation is compliance with standards or internal policies. Physical design is a significant piece of this.

Common data centre security measures include:

- Perimeter fencing and CCTV coverage.

- Access control with badges, biometric checks or mantraps.

- Visitor logging and escorting procedures.

- Locked racks or cages for customer equipment.

These do not only matter for compliance. They reduce the chance of accidental or malicious physical interference with equipment.

Environmental and power controls in standards such as PCI DSS

Standards like PCI DSS (for card payment data) expect that critical systems are housed in environments with controlled access and protected from environmental hazards.

Requirements often touch on:

- Power and cooling continuity.

- Fire detection and suppression.

- Environmental monitoring and alarm response.

- Documented procedures for maintenance and incident handling.

The PCI Security Standards Council publishes the PCI DSS documentation with exact wording, but a well run professional data centre will typically be designed with these principles in mind.

What to look for if you handle card data or other regulated information

If you are responsible for card data or other regulated information, look for:

- Evidence of relevant certifications or audits for the facility or provider.

- Clear descriptions of physical and environmental controls.

- Support for segregated environments, such as dedicated racks or VLANs.

- Services that explicitly address the needs of regulated workloads, such as PCI conscious hosting.

Bringing your hosting provider into early conversations with your security or compliance team can prevent misunderstandings later.

Practical Checklist: Questions to Ask Your Hosting Provider About Power, Cooling and Network

Quick question set for SMEs choosing managed hosting or VDS

If you are an SME looking at managed hosting, VPS or VDS, these questions are a useful starting point:

- “Is the data centre designed with N+1 or better redundancy for power and cooling?”

- “Do my servers or virtual machines benefit from dual power feeds and redundant network paths?”

- “Which network carriers do you use, and how do you achieve path diversity?”

- “How do you protect against hardware failure on my primary server? Is there a failover option?”

- “What monitoring and alerting do you use for my environment?”

- “For managed services, which parts of the stack do you take responsibility for, and which parts remain with us?”

Used together, these questions help you understand both the facility and the managed service overlay.

How to interpret the answers and spot vague marketing

A few signs that the answers you receive are meaningful:

- They refer to specific designs (“Each rack has two 32A feeds from separate UPS systems”) rather than only to abstract terms.

- They acknowledge trade offs and limits (“We do not provide cross data centre failover on this plan, but we can design it as a separate project”).

- They are comfortable discussing past incidents and what changed afterwards.

By contrast, be cautious of answers that:

- Only repeat SLA percentages or buzzwords without explaining how they are achieved.

- Dismiss your questions as unnecessary for your size of business without giving you the context to decide for yourself.

When to step up from simple hosting to a more resilient setup

Signs that it might be time to move from basic hosting towards a more resilient design or managed environment include:

- Outages now have a clear financial or reputational cost, not just inconvenience.

- Your team is small and already stretched, yet you are managing complex multi server or multi site setups yourselves.

- You are starting to take online payments at scale, or to handle regulated data.

- Traffic is growing and you see regular performance issues during peaks.

In these cases, using managed hosting or virtual dedicated servers can offload a significant operational burden. The aim is not to remove your control, but to let you focus more on your application and less on the low level mechanics of failover and capacity.

Next Steps: Turning Data Centre Resilience into a Hosting Plan

Matching resilience needs to hosting models and budgets

The right level of data centre resilience is not “as much as possible”. It is “enough for your risk tolerance and budget, with a clear understanding of what happens when things go wrong”.

As you plan:

- Start with the business impact of downtime in different scenarios.

- Choose a facility and provider whose physical design and processes are proportionate to that impact.

- Design your hosting architecture on top of that foundation, from single server through to multi site if needed.

- Invest in backups, monitoring and incident response as non negotiable building blocks.

Where managed WordPress, WooCommerce and VDS fit into the picture

For many organisations, especially those running WordPress or WooCommerce as their main public presence, the natural progression looks like:

- Start on shared or basic VPS hosting.

- Move to managed WordPress or managed VPS as traffic and complexity grow.

- Adopt virtual dedicated servers or multi server designs when uptime and performance become central business concerns.

At each step, a provider can take on more of the operational responsibility: managing updates, tuning databases, configuring failover, and handling the details of data centre integration, while you keep control of your application logic and content.

If you are serving a global audience or large media libraries, combining resilient hosting with something like the G7 Acceleration Network can also help by improving web hosting performance features at the edge, reducing image weight and smoothing out traffic peaks.

Where to read next on redundancy, uptime and disaster recovery

To build on what you have read here, you may find these follow on articles helpful:

- High Availability Explained for Small and Mid Sized Businesses for a practical view of high availability setups.

- From Backups to Business Continuity: Building a Realistic Disaster Recovery Plan with Your Hosting Provider for turning these concepts into a concrete recovery plan.

If you would like help matching your resilience needs to a practical hosting design, you are welcome to talk to G7Cloud about architectures, managed hosting options or virtual dedicated servers that fit your level of risk and in house capacity.